Lovingly also known as “peeps”, the Western Sandpiper is among the most colorful and beautiful of all the Sandpipers found in North America. They are a spectacle to be marveled at, gathering in enormous flocks of hundreds of thousands during their spring migrations. The sight of these golden and rufous hued shorebirds is so breath-taking that they attract millions of visitors in Alaska and California who hope to witness one of nature’s greatest performances for themselves.

About Western Sandpipers

These shorebirds nest in the remote regions of the Arctic and mostly migrate along the Pacific Coast to reach their wintering destinations. They are long-distance migrants that may travel to regions as far as Peru during the winters. These sandpipers are also latitudinally segregated by sex, body size, and age during the winters, with many more females found in the southernmost regions of their wintering range and more males wintering in the north. This is an interesting trend since it is not a commonplace occurrence among most shorebirds. Western Sandpipers are undoubtedly some of the most popular Sandpipers there are. Today, we will be diving into the lives of these magnificent birds.

● Western Sandpiper Photos, Color Pattern, Song

● Western Sandpiper Size, Eating Behavior, Habitat

● Western Sandpiper Range and Migration, Nesting

GET KIDS BIRD WATCHING

Western Sandpiper Color Pattern

Western Sandpipers have clear differences in their plumage depending on the season. Their non-breeding plumages are a uniform gray to brownish-gray, with the feathers fringed with pale markings and a whitish forehead, and small white eyebrow-like marks. Their flight feathers have white tips, and their inner wings form a wing bar. The primary and secondary flight feathers are dusky, with paler grayish markings on the inner areas. Their rump and their upper-tail feathers are a dark brown, while the lower parts of their tail are white, this forms a distinct pattern when they are in flight. Their underparts are white and have fine streaks of gray throughout the breast.

Western Sandpiper breeding plumages are relatively more vivid, with their upper parts exhibiting a mixed blackish, buff, whitish, and rufous. Their flight feathers are showcase strong, rusty fringing that matches with similar patterns on the sides of their crown, nape, and rear ear coverts. Their crown is rufous, and their ears have dark flecks. Males are generally bright and have more extensive rufous on their upper parts and crown when compared to females. Females, on the other hand, have more intense streaks on their underparts. Juveniles look similar to their nonbreeding plumages but have whiter underparts and brownish-gray feathers on their neck, breast, sides, and flanks.

Description and Identification

These birds are common in tidal areas where they join other shorebirds that forage on mudflats during low and middle tides. Since they forage at undisturbed locations, it is hard to spot them with the naked eye and even harder to distinguish them from other shorebirds. You can also find them inland in regions like flooded habitats, sewage ponds, and muddy lakeshores. You can often hear them before you see them, with their loud squawk-like calls generally giving their presence away.

Western Sandpiper Song

The most common call let out by these sandpipers is the loud “chee-rp, cheep! or chir-eep”. It resembles the squawk of Robins and both sexes make this call while in flight. Birds on the ground also use it before the entire flock takes off for the air. Flushing birds also have a similar note that is softer, best transliterated as a “chir-ir-ip”. Individuals that are in unpleasant situations that bring them to fear or anxiety also give out loud distress calls to catch

the attention of surrounding birds.

Their songs begin with a “tweer tweer tweer” that ascends in pitch before it ends with a descending buzzy trill. The initial notes have a high, thin, and ringing quality to them, while the second half has harsher and a more contrasting quality. They often weave a long, grating note that sounds like a “brrrt, brrrt, brrrt” into the song. These songs are generally during courtship. Courtship also includes high-pitched chase calls that sound like “ti ti ti”. Another extremely common call is their alarm call, a series of short, trilled notes that are let out when predators are in the immediate vicinity of the brood. Sometimes it is followed by the broken wing display that is accompanied by a convincing distress call to distract the attention of the predator away from the brood. The vocalization of juveniles is severely understudied, leaving us with very little information to work with in order to understand their vocal development.

Western Sandpiper Size

Western Sandpipers are small shorebirds that have a body length of 5.5-6.7 inches and a weight of 0.8–1.2 ounces. They have a long, thin bill that is slightly curved at the tip, along with medium-sized legs and a short tail. Their long, pointed wings have a wingspan of 13.8–14.6 inches. Females generally tend to be larger and longer-billed than males. These proportions make them larger than Least Sandpipers but smaller than Dunlins.

Western Sandpiper Behavior

Western Sandpipers spend most of their time on land. They prefer to walk or run while they forage, and often stand one leg and hop. Sometimes, their habit of hopping on one leg gives them the misconception that they are crippled birds. However, although they like to spend most of their time on land, they are extremely strong fliers that can travel up to 620 miles in a single day. Their narrow, pointed wings aid them in reaching extremely high speeds. They are also able swimmers, with chicks often swimming in shallow ponds to escape predators before they learn to fly.

Fights are pretty common between breeding males in their territories. Physical interactions are common, with the defending and the intruding birds charging at each other and then fluttering above the ground almost immediately after. As they take off into the air, they begin slapping each other with their wings. These fights can cause injuries, with feathers often tearing off both birds. Although most fights last a few seconds, some can last from many minutes to a few hours. Although they are less aggressive during the winters, they most likely still get into conflicts over food at their wintering grounds.

Western Sandpipers are strictly monogamous, with a very small percentage of the chicks in a single brood tracing their parentage to more than 2 parents. Both males and females chase away intruders from the nest site and collectively take responsibility for incubating the eggs. However, females generally abandon the brood before they fully fledge, leaving the males to mainly raise the chicks. Males generally arrive at the breeding grounds before the females begin establishing their territories prior to mate selection. When the females arrive, males begin to display in the air while calling out to catch their attention. After getting ignored for a couple of days, females finally follow males into the air to cement their bond.

Western Sandpiper Diet

These birds follow a diet that is comprised of insects, spiders, and aquatic invertebrates. Throughout the year, their diet changes depending on the availability of prey. They feed in or at the edge of shallow water about 2 inches deep, often consuming insects and their larvae along with it. Some sandpipers also eat “biofilm”, a frothy, scumlike mixture of diatoms, microbes, organic detritus, and sediment. Other prey items include spiders, midges, craneflies, brine flies, shore flies, water beetles, marine worms, roundworms, and amethyst gem clams. They also eat Baltic clams, blue mussels, eastern mudsnail, brine shrimp, and other tiny crustaceans like amphipods and copepods.

Western Sandpiper Habitat

These birds nest only in the relatively drier tundra habitats, from coastal lowlands to the lower parts of mountains. Areas like these are typically dominated by dwarf birch, willow, crowberry, and many kinds of sedges, grasses, and lichens. Their foraging habitats are also usually away from their nest sites in coastal lagoons and tundra ponds where water is less than 4 inches deep. They may also catch insects near the nest site. During migration season, they use similar habitats along with river deltas, muddy rivers, and lake margins. They also use sod farms, sewage treatment ponds, salt marshes, and freshwater marshes. Wintering birds use similar habitats but also use salt evaporation ponds and abandoned shrimp farms, or around high elevation lakes if further inland.

Range and Migration

They mainly breed in eastern Siberia and Alaska, before migrating over both coasts of North America and South America, along with the Caribbean to their wintering destinations spread throughout Mexico and the Caribbean.

Western Sandpiper Lifecycle

After breeding, these sandpipers have their only brood of the year. Each brood has a clutch size of 2–4 eggs, with both parents taking turns incubating eggs for around 21 days. Although females begin by giving the eggs more attention, males take on that responsibility soon after. The chicks emerge from their eggs covered in down and are capable of leaving the nest within a couple of hours. Their mothers generally leave after a few days while the fathers stick around. The young are generally able to feed themselves far before they are independent. They learn to fly at around 17–21 days and become independent after that.

Nesting

Males find and prepare the nest sites in their breeding territories, while females are responsible for making the final selection regarding the nest site. Sites are generally flat, scraped-out depression in a patch of dry tundra. The construction of the nest is done by both members of the pair, with males and females arranging dry willow leaves, birch leaves, grasses, sedges, and lichens in the scrape. The scrape generally sits below a grass tussock or dwarf birch. The resulting proportions make them about 2.5 inches across and 2.2 inches deep.

Anatomy of a Western Sandpiper

Western Sandpipers are small shorebirds that have a body length of 5.5-6.7 inches and a weight of 0.8–1.2 ounces. They have a long, thin bill that is slightly curved at the tip, along with medium-sized legs and a short tail. Their long, pointed wings have a wingspan of 13.8-14.6 inches. Females generally tend to be larger and longer-billed than males. These proportions make them larger than Least Sandpipers but smaller than Dunlins.

Final Thoughts

Surveys of their numbers have found that their numbers have not suffered drastic declines, indicating a species of low conservation concern. Population trends are not known. The draining of wetlands in Middle America for shrimp farms and other purposes continues to reduce available habitat on the wintering grounds. In California, the spread of non-native cordgrass has also reduced the habitat available for wintering and migrating Western Sandpipers. Pollutants pose conservation risks to this species throughout its range. The effects of climate change, including rising sea levels and changes to Arctic habitats and food webs, are forecast to reduce available foraging habitats and prey in the near future.

Western Sandpipers are some of the most popular sandpipers in North America. Their huge flocks that migrate to their wintering grounds make for some of nature’s finest spectacles, with often equal numbers of human visitors gathering just to catch a glimpse of them. Not only are they simply beautiful, but they also have nomadic personalities that make them all the more enigmatic. This is why conservation efforts need to be leveled up. Treasures like these remind us that if things do not change right now, future generations might not get to experience the treasures we experience.

Ornithology

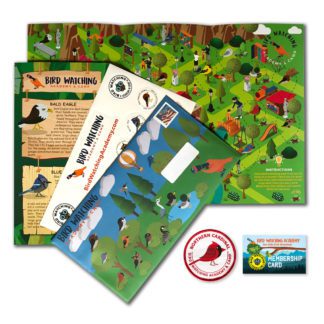

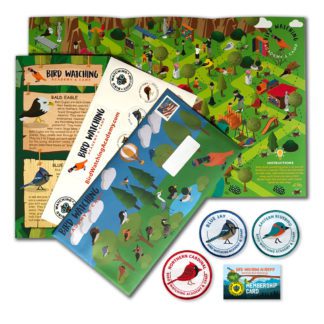

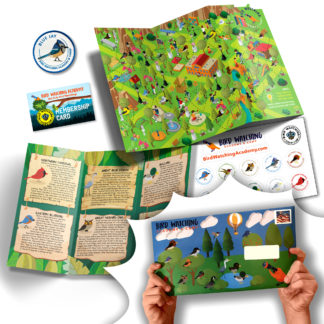

Bird Watching Academy & Camp Subscription Boxes

At the Bird Watching Academy & Camp we help kids, youth, and adults get excited and involved in bird watching. We have several monthly subscription boxes that you can subscribe to. Our monthly subscription boxes help kids, youth, and adults learn about birds, bird watching, and bird conservation.

- Kids Bird Watching Monthly Subscription$10.00 / month

- Kid & Adult Bird Watching Starter Pack Subscription$10.00 / month and a $72.00 sign-up fee

- Kids Bird Watching Starter Pack Subscription$10.00 / month and a $19.00 sign-up fee

Bird Watching Binoculars for Identifying Western Sandpipers

The most common types of bird watching binoculars for viewing Western Sandpipers are 8×21 binoculars and 10×42 binoculars. Bird Watching Academy & Camp sells really nice 8×21 binoculars and 10×42 binoculars. You can view and purchase them here.

- Birding Binoculars$49.99

- Kids Binoculars$13.99

Western Sandpiper Stickers

Stickers are a great way for you to display your love for bird watching and the Western Sandpiper. We sell a monthly subscription sticker pack. The sticker packs have 12 bird stickers. These sticker packs will help your kids learn new birds every month.

Bird Feeders For Western Sandpipers

There are many types of bird feeders. Bird feeders are a great addition to your backyard. Bird feeders will increase the chances of attracting birds drastically. Both kids and adults will have a great time watching birds eat at these bird feeders. There are a wide variety of bird feeders on the market and it is important to find the best fit for you and your backyard.

Bird HousesFor Western Sandpipers

There are many types of bird houses. Building a bird house is always fun but can be frustrating. Getting a bird house for kids to watch birds grow is always fun. If you spend a little extra money on bird houses, it will be well worth every penny and they’ll look great.